Wild Love

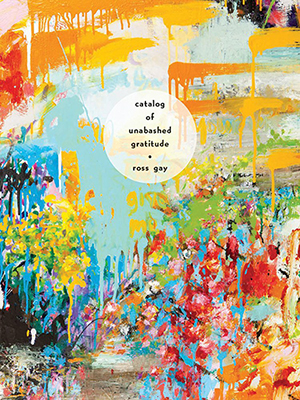

Like many other poets, Ross Gay has a creative practice that extends beyond literature. In his most recent collection, Catalog of Unabashed Gratitude, he turns his eye toward gardening—the flowers, fruits, and sense of community therein—a practice that has consumed his imagination and inflected his worldview. Gay is an associate professor of creative writing at Indiana University in Bloomington, where he is also a member of the city’s Community Orchard. When we spoke, his poetry and gardening worlds had converged once again: Catalog was named a finalist for the National Book Award as Gay made his way to the Black Farmers & Urban Gardeners Conference in Oakland, California. The following exchange was edited and condensed.

Is gardening in any way secondary to your life as a writer?

Not at all. It’s central to my life—now. It wasn’t always. I’m a new gardener. It’s only the last seven or eight years I’ve been doing it. But it’s totally what I do. I think part of why I feel so connected to that kind of work, besides the sort of fundamental, human connection to plants, is the sort of analogous, transformative experience that working with plants, growing things, has to making metaphor. Planting a garden is very much imagining something that’s not there. Which is kind of like a metaphor—linking things that previously had not been linked. I can see the connection between the two and that they satisfy that dreamy, imaginative part of myself in a similar way.

What do you mean by that—imagining something that wasn’t there?

You’re putting something in the ground that is both entirely different from the thing which will arrive and entirely the same. It’s precisely two things or more at once. It’s like time travel too. Which is what metaphor is. It’s saying that these two things are true, simultaneously.

Why did you start gardening?

There are probably a bunch of reasons. One is that I was and am involved with a gardener. Another was that I moved to a place where people were gardening all over, all around me. The third and maybe … I don’t know—it feels like it was a real pressing concern at the time—is that one of my best friends, his family was about to move out of our hometown, and his father was and is a beautiful gardener and had these fig trees, and I needed to transplant those fig trees so I could keep some of my hometown in my life. So I transplanted those fig trees. And I remember very much when I was looking for a house that I was looking for a place where I could put these trees. And those trees are there. And they’re all around Bloomington, Indiana, actually.

How does building a garden compare to building a poetry collection?

When I garden, I think about the foods that I really love, that I adore, and want to eat and want to take care of as plants. I think about how much space I have. And I think of things like light. I think about how the gathering of plants will relate to each other. So for instance, I have a whole row of beans planted. I’m not going to follow that with garlic because I understand that garlic and legumes don’t grow very well together. So I’ll probably put the garlic someplace else. And I’ll probably follow those beans with some greens so they can shoot off the nitrogen that’ll be left in the soil from the beans I’ve been growing. I try to grow plants that will complement and nourish one another. So around all my fruit trees, I have plants like comfrey that grow their own fertilizer and die on top of the soil to feed the trees. I also think about stuff that’s going to be fun to eat with other people, that will grow enough and make enough and maybe I can share.

All three of my books have been very different to make. But there are these sorts of things that are overlapping. Obviously, I want to be delighted by my poems. I want to include poems in a book that I should love. And that I hope might delight someone else. I also think very much about how poems are relating to one another and their interactions and how a given poem might make another poem more of what it is or if it needs to be less of what it is. Is it possible that a poem can behave in some way as a good complement? I think that’s always one thing I think about when I’m ordering poems. Can a poem earlier in the collection make a poem later in the collection possible or more likable or intelligible?

The other thing, and this is the truth-truth, is that there’s a degree of intuition involved. If you could go through my various notebooks that have anything in them, including poems, including notes on a book on farming I’m writing, you’d find little drawings of gardens and plants. They’re incredible. I think you’d think I really knew what I was doing. Because I have all the space laid out real good, and this tree is going to be like, 15 feet away from that tree, and this is going to be here and this is going to be there. My garden is awesome, but it does not look like that. [laughs] It’s designed—it’s really designed—but that design is intuitive. And it’s constantly merging and changing and evolving. And I think there’s a degree of organizing a book that also feels like that. Like, this feels right here. I hope it’s going to work.

There’s a lot of grief in Catalog, but there’s also a tremendous amount of joy. By the time I got to the poem “Weeping,” about the niece who’s made a friend in this butterfly, I was thinking, “I’m reading a book of poems about flowers by a black man.” Even though you do talk about things related to race, I wondered if perhaps you were resisting all the things you could talk about. Or all the things people might expect from you. Was any of that conscious, or were you just minding your business talking about your regular life?

If there was any kind of overt action the book is taking—and I don’t want it to be a book against anything; it’s a book imagining or advocating for something—it’s really, like the title says, it’s advocating for something unabashed, something vulnerable and, you know, full-on. If it’s conscious of any sort of confinement, it’s a confinement that I often feel when I want to express a sort of wild love. When I want to be full-on about what I adore. And that’s maybe what the book is most—it has that kind of heart in it. It wants to be nuts-in-love with shit. Which includes being heartbroken, all torn up about stuff. And open. And that can feel really terrifying, that kind of real openness or attempt at openness—I’ll speak for myself—that feels scary. When you’re like, “Oh, I love this,” because then if someone’s like, “Fuck your little thing,” that sucks, that hurts. The posture of irony is emotionally easy to take. It’s very much a way of not being vulnerable, not being at-risk.

I was also thinking about the length of the poems. There are a couple times you reference being long-winded. What is that about? It’s not just gratitude—it’s a catalog. The poems are very long. Why were you drawn to that form?

Again, I think it’s part of that full-on-ness. Being all in about expressing one’s delight and one’s care and one’s love while being acutely aware that a lot of people are going to be like, “Dude, shut the fuck up already.” And I feel like that very much informs the poems. An awareness of like, “I know. I know this is going to get annoying or tedious” or “I know you don’t care how much I love this thing.” There’s also probably some kind of acknowledgment of poetic craft sensibility, which is often about excision and “best words, best order” or whatever. And tightening, tightening, tightening. This is a little bit like, “This isn’t tight. This is kooky.”

One thing a garden can do that maybe poetry can’t is have an everyday use. How do you think about beauty, or art, versus something whose purpose is practical?

Well, I would argue with that and say that the poems and the art I turn to have a very practical use, and probably in ways that manifest themselves in my body, as a version of nourishment. I have a feeling if there was some kind of tool that we haven’t invented yet, and I’m listening to a poem by someone I love—you will see a kind a cellular response that will be in some way not unlike if I ate a bowl of greens and chickpeas, or something. Though I want to say that there are, in fact, practical applications. I also think poems are one way we exercise our capacity for imagination and for metaphor. And those are the things by which we actually survive. Those are the ways by which gardens are planted.

Kyla Marshell is a writer whose poems and other work have appeared in Blackbird, Calyx, Gawker, the Guardian, SPOOK magazine, Vinyl Poetry, and elsewhere. Her work earned her Cave Canem and Jacob K. Javits fellowships and an MFA in creative writing from Sarah Lawrence College. A Spelman College graduate, she is the the former development/marketing...

-

Related Collections

-

Related Authors

- See All Related Content

Yes, metaphor is practical; and I think, goes beyond what

we even think it's possible to be. We may discover how

metaphor can help us move foward in understanding physics

(how standard particle theory and multiverse ideas can

both be true)--if we allow ourselves to be open to new

paradigms. Our future depends on combining and connecting

disciplines. Metaphor is one of the biggest tools we have

for doing this.