Who Did This?

Last spring, a private poetry exhibition spilled out on my kitchen table when I opened a manila envelope stamped “the final issue finally.” It arrived in my mailbox from the poet Ken Mikolowski—the co-founder, with his late wife, Ann, of The Alternative Press (TAP). The Mikolowskis were part of the Detroit Artists’ Workshop, a community of artists, poets, and musicians who lived and worked in Detroit in the 1960s. From 1969 until Ann’s death in 1999, the couple published TAP, a semiregular “magazine” that was actually numbered packets of poetry and art, sent out three or four times a year. Using an old letterpress in their basement, the Mikolowskis printed poetry in the form of everyday items—bookmarks, postcards, bumper stickers—and mailed them out to their few hundred subscribers.

The envelope was the last “issue” of TAP, which Ken sent to TAP’s subscribers—and to me, because I was working on a series of articles about him and Ann and their work. I spread out the contents. Here was a gorgeously hand-set, hand-printed broadside of one of Allen Ginsberg’s final poems, one of many printed for his memorial service in Ann Arbor in 1997. Beside it was a poetry bookmark by Hettie Jones that read “Song at Sixty: If you want to know me / you better hurry.” A poetry broadside by Sherman Alexie called “The Museum of Tolerance” served as a table mat for a dozen or so poetry postcards.

Mixed in with the meticulously typeset, letterpressed poems were handwritten postcards, some bearing poems, some with artwork as well. On one, for example, I could barely decipher a few lines of a poem by Anne Waldman, written on a scrap of notebook paper pasted on a postcard,

Sirens in the meadow

“Beat book – Ferlinghetti.

Write Lawrence about Dorn books

This poem is a dashed-off note to herself, the equivalent of an item in a day planner; besides the poet, I am its one and only reader. Waldman’s poem is part of the Multiple Originals project, a poetry and visual art postcard project that was a brilliant, all-but-forgotten subset of the TAP endeavor. It began in 1971 when Ken Mikolowski and his friend Gordon Newton, a Detroit visual artist, were kicking around ideas for another way that the writers and visual artists of the Artists’ Workshop could collaborate. The idea seemed simple enough: Poets were asked to write 500 original poems, one on each of a numbered set of 500 postcards. The postcards were blank except for a poet or artist’s name, which the Mikolowskis stamped on the back—they were like 500 three-by-five-inch canvases. Poets could collaborate with anyone they wanted to, or work solo. When poets finished a batch, they sent them back to the Mikolowskis, who would let them pile up until they’d printed a bunch of the other stuff—ever more fanciful, elegant letterpress and offset poetry in all types of formats (bumper stickers, tea bags, bookmarks, broadsides, calendars). From the two piles, they divvied up the poetry for their subscribers, slipping a handful of printed poems and original poetry postcards—each written by a different poet—into a manila envelope. TAP published three or four of these “issues” every year or so. The playful genius of Mikolowski and Newton’s idea cartwheeled from Detroit outward, shaking something loose in American poetry during the doldrums of the 1970s. Soon several dozen poets affiliated with many different schools—the Beats, Black Mountain, the New York School, and Cass Corridor poets—began sending packets of postcards back and forth across the country, sometimes in collaboration with visual artists. Robert Creeley signed on. On postcard 29 of his first of two sets (!!) of 500, he joked:

One

to a customer.

The contours and strictures of the form suited Creeley, who ended up writing a thousand short, wry lyrics, including:

Never

the less.

Ted Berrigan decided to do a batch, too. Alice Notley, his wife and fellow poet, told me recently:

Ted hadn’t been writing much, and saw right away that it was a useful project to use a postcard as a form, and as a way of living the life of a poet. It was very communal. He carried them around with him, asking friends he visited for a line. People also came over to the house a lot. He would make them write a line or two. I gave him a lot of lines. We also played back and forth with them with Anselm and Edmund [their sons].

Gravely ill, Berrigan wrote the postcards, his son Anselm told me recently, as “someone enraged and loving who is about to leave.” He used them to speak bluntly, to settle disputes, to pay homage to literary forebears, to mull over mortality, and to wrap up his life’s work. Berrigan made copies of his poems before sending them to the Mikolowskis, and assembled 100 of them into a manuscript that was published posthumously as A Certain Slant of Sunlight.

Of course, the communal could turn competitive. On receiving his first stack of 500 blank cards from Ken and Ann, poet Bill Berkson wrote back to them:

Just testing— these cards are perfect —and I’ll do right by them, whatever that may be. Talking it over with Creeley, he said “500 poems.” So I assume he means business. Well, who doesn’t. Full steam. . . .

Then Ted Berrigan upped the ante:

You guys have the courage of my convictions. Thank God! We’ve been flu-ridden, nevertheless Alice has done 75 postcards, and I’ve done 67, so far. And we’re both getting about 5 a day, sometimes more done after a slow start—nearly all new writing—Alice is doing lots of painting on hers and mine are “getting” more than words on them, too. We both aim to break Bill B.’s record!

The activity might have seemed easy and achievable in the moment, but while many poets signed on, most soon ran out of breath after 50 to 100 poems. “Oh my!” John Yau recalls thinking. “A great idea, but midway through I was tested. Five hundred poems are, after all, 500 poems.” Andrei Codrescu recalls:

I started writing 500 poems on postcards with art by my Alice on the front; we were breaking up at the time, so we thought that it would be (unfunnily) amusing if we called the series “Just Married.” Alice did all her art, conscientious person that she is, but I only got out about fifty scribble-works before we halted.

Be Here Now

Several months after the final issue arrived in my mailbox, I traveled to Ann Arbor to visit the TAP archives at the University of Michigan. Ken had rescued one or a handful of Multiple Original postcards by each poet from possible oblivion for future scholars and critics. The library has neatly categorized them into file folders labeled with each poet or artist’s name. Like Berrigan’s poems in the archives, many of the poems bear the stamps, not of Paris or Brazil, but of daily life—interactions with family and friends, names of visitors, worries over money, spats, street scenes outside windows, grocery lists. These reports on the immediate, sent from anywhere in the country and internationally, capture a historical moment—the utopian ideal that life is best lived in the present. These poems are not antiseptic spaces that wall off the mundane. Instead they welcome it, staying true to the ephemeral. Occasionally the ephemeral coalesces into a poem that is more lyrical; here’s one by Anne Waldman, which at first reads like a message on a postcard that anyone could send from a beach holiday:

light mostly

the white blouse

more sun and the girl selling ice cream

there on the beach

skirt caught

the wind hugging its visibility

Format vs. Content

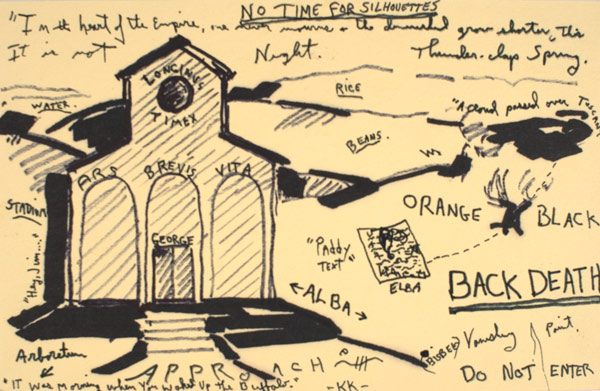

Some of the most stunning postcards are collaborations between poets and visual artists, or by poets who are also visual artists, who play with the format.

In a postcard in the University of Michigan library titled NEGATIVE, created by Philip Guston on which he used a poem by Bill Berkson, a light bulb hangs from a chain—possibly the symbol of an artist’s initial idea. It illuminates a spare space with square geometric shapes—which mathematically measure volume. A variation of a shape becomes a door with one shoe poking out. In Berkson’s prose poem on the postcard, a person in a restaurant contemplates whether a door being pushed open and one being pulled shut exert the same force. The restaurant empties of people. The speaker wonders “if just holding it [the door] wouldn’t involve exactly the same level of force.” The postcard and its objects are filled with substantial weight on the one hand, and with emptiness on the other.

A collaborative postcard by poet Donna Brook and visual artist Jim Pallas, also in the library collection, shows a woman with her back to the reader pushing a baby carriage into the white space, as if moving away from the reader. A shipping label pasted below reads, “CONFIRMING ORDER / Do Not Duplicate Shipment.”

Donna Brook also did a series of 500 poems about rabbits:

Ken told me I couldn't do 500 on rabbits, so I took up the challenge—I had rubber stamps made up that included Bunny, Pseudobunny, Nonbunny, and just went with it. I remember my mother and I taking photographs of carrots that we arranged on our deck in a rented house on Martha’s Vineyard.

Alice Notley thought of the postcards as “small pristine white spaces.” As a visual artist and poet, she found that the postcards made the process of writing material as opposed to solely abstract. Could she keep the space pristine, or was she going to accidentally mess it up? In the folder labeled “Alice Notley,” I found a postcard adorned with a drawing, in child’s crayon in bright primary colors, of a ferry boat bobbing on green waves.

TED

He’s on the boat

in my heart

the sky part

On earth

we have only

his picture:

ourselves

She composed this poem with her two sons after Berrigan died. At that time, when Alice thought she might never write again, Ken helped her by sending her a second set of postcards. Many of them were grief notes, messages sent to Berrigan that convey the unreal certainty that after a loved one dies, the daily chitchat continues. In them you can hear Alice thinking through the bewilderment of still being in a relationship with someone who occupies neither place nor time, yet still somehow does.

this person who sleeps in my bed

she’s slept there forever and yet

there was another

when it was another

bed looking so same so recently

but that I would have to remember

strangely an involuntary measure)

(from “Sweetheart”)

A few of the poems from the second set were later published in her book At Night the States, but in between the covers of a book, they lack the physical energy of the original poetry and art postcards. A poem such as “Sweetheart” might be accompanied by a whimsical portrait of herself. On the Berrigan postcards at the library, you can make out the handwriting of a line by Bernadette Mayer, Eileen Myles, or Alice Notley that inspired his poem. Some lines served as impetus, others as digressions. In A Certain Slant of Sunlight, their multiple authorship is erased.

Looking through the Multiple Originals postcards at the library, I realized I was holding fragments of an artistic project, the whole of which can never be collected or studied. These poems had escaped the museum of literature. Many of those that remain are like charcoal smudges on a nearly completed portrait, or the hint of a form emerging in repeated sketches of a single idea. Scrawled mishaps. Such early attempts are commonly displayed at major retrospectives. Some of them are works of art in their own right. In them, we can see talent working against the pressure of time and the flux of everyday life. The sense of art being made and the presence of the person in these artifacts can be more fascinating than the finished piece hanging labeled on the wall.

Today, few people in the art or literary worlds know of the Multiple Originals project. As the poet and art critic John Yau told me, “The Multiple Originals project opened a new vein for poetry that literary and art critics have yet to learn about or grapple with.”

There are other postcards out there. Hoping to find some, I asked everyone I interviewed if they had kept their issues of TAP. “Absolutely!” they said, but no one could locate them. In file cabinets and storage boxes across the country, there might be original poems by Creeley, Waldman, Notley, Berrigan, Berkson, and many other American poets. If they’re found, they would add to our understanding of the playful genius of the Multiple Originals as a collaborative project, and to our understanding of the oeuvre of the poets who participated in it. As Robert Creeley once said about the project, “This will screw up my bibliographers.”

Emily Warn was born in San Francisco and grew up in California and Detroit. She earned degrees from Kalamazoo College and the University of Washington. Her full-length collections of poetry include The Leaf Path (1982), The Novice Insomniac (1996), and Shadow Architect (2008). She has published two chapbooks: The Book...

-

Related Podcasts

-

Related Authors

-

Related Articles

- See All Related Content

View a slideshow of Alternative Press postcards

View a slideshow of Alternative Press postcards

I did about 320 multiple originals for that last issue. I thought I was

breaking the rules and kept copies of most of them. But I lost the copies

within a couple of months--so even they are scattered somewhere.