“Wake Up! Wake Up!”

Harriet Monroe’s own words below are italicized and taken from her reviews in the Chicago Daily Tribune. Read from Monroe’s review, “Sermon for Good Americans Found in the Art of the Art Galleries.”

In her art reviews, Harriet Monroe addressed not only individual artists and artworks, but also the creative process generally. She spoke about the inspiration and challenges of creativity, the duties of the audience, and the role of the critic. Many of her pronouncements and arguments relate to her editorial decisions at Poetry: A Magazine of Verse, which she founded in 1912; indeed, she continued writing art columns for a year and a half afterward.

In this period of her career, Monroe was thinking about creativity in all its expressions, including through artists and poets. She chronicled the Chicago art scene in her Chicago Daily Tribune reviews while considering submissions of verse for publication in her own magazine.

Wake up! Wake up! use your eyes! Know a good thing when you see it; and, knowing it, recognize that it is your sacred duty, and ought to be your pleasure, to encourage the creator of that good thing … to show you the beauty of your own life and environment.

Monroe was an accomplished poet and still composed verse of her own. She primarily considered herself an artist, rather than solely an editor or critic, and so her beliefs about creativity and art were that of a practitioner. Her penchant for lyrical language fills her Tribune columns, and many of her descriptions of artworks and observations are uniquely poetic, making them not only critically thoughtful but metaphorically illustrative.

Monroe was clear about the importance of art and the reasons art, poetry, and those who produce them must persist. The trials of founding Poetry: A Magazine of Verse, including the financial struggle of establishing a magazine business, forced Monroe to reflect on the nature of creative success, and reviewing the radical paintings in the Armory Show provided her with an outlet to address it.

She wrote vividly about the nature of creative inspiration and employed the traditional feminine trope of the muse, saying how [H]e must follow his particular goddess [of inspiration]. She described the rigors of the creative life in Biblical terms: Sackcloth and ashes, fasting and prayer, long years in the wilderness—these are a necessary discipline for certain souls. But few are strong enough to accept it. And there are dire consequences for falling short: If he does less than this, he is faithless and she [inspiration] will not remember him. Even commercial success had its own challenges: If he hands her over to the money mad, speed mad chauffeur she will ironically make a salesman of him, perhaps insult him with orders and dollars, with flattery and popularity.

For Monroe, creativity was work, and artists of all disciplines needed to court and be true to their inspirational sources before and after they produced genuine and enduring creations. The result for painters might be works so moving that they could be likened to poetry.

Art Reflecting the “Deep Poetry of Life”

Monroe often used the word poetic to describe visual artists’ works to suggest something ineffable or transcendent. She lauded one painting by the American artist, George Fuller (1822–84), as a great picture, ... and one of the most poetic ever painted in America. Less grandly, but just as flatteringly, Monroe described a crouching figure sculpture by Enid Yandell (1869–1934), as a dreamy, poetic little thing. In Monroe’s mind, an artist’s work could not be successful without this quality.

Life, too, was suffused by a sense of poetry, and artworks that captured it had the capacity to encourage viewers toward an ennobled existence. About the paintings of the Chicago artist Karl Anderson (1874–1956), Monroe wrote that he has ... something high and true to say about the deep poetry of life, and he says it with full rhythmic emphasis and with beautiful and brilliant clarity of color.

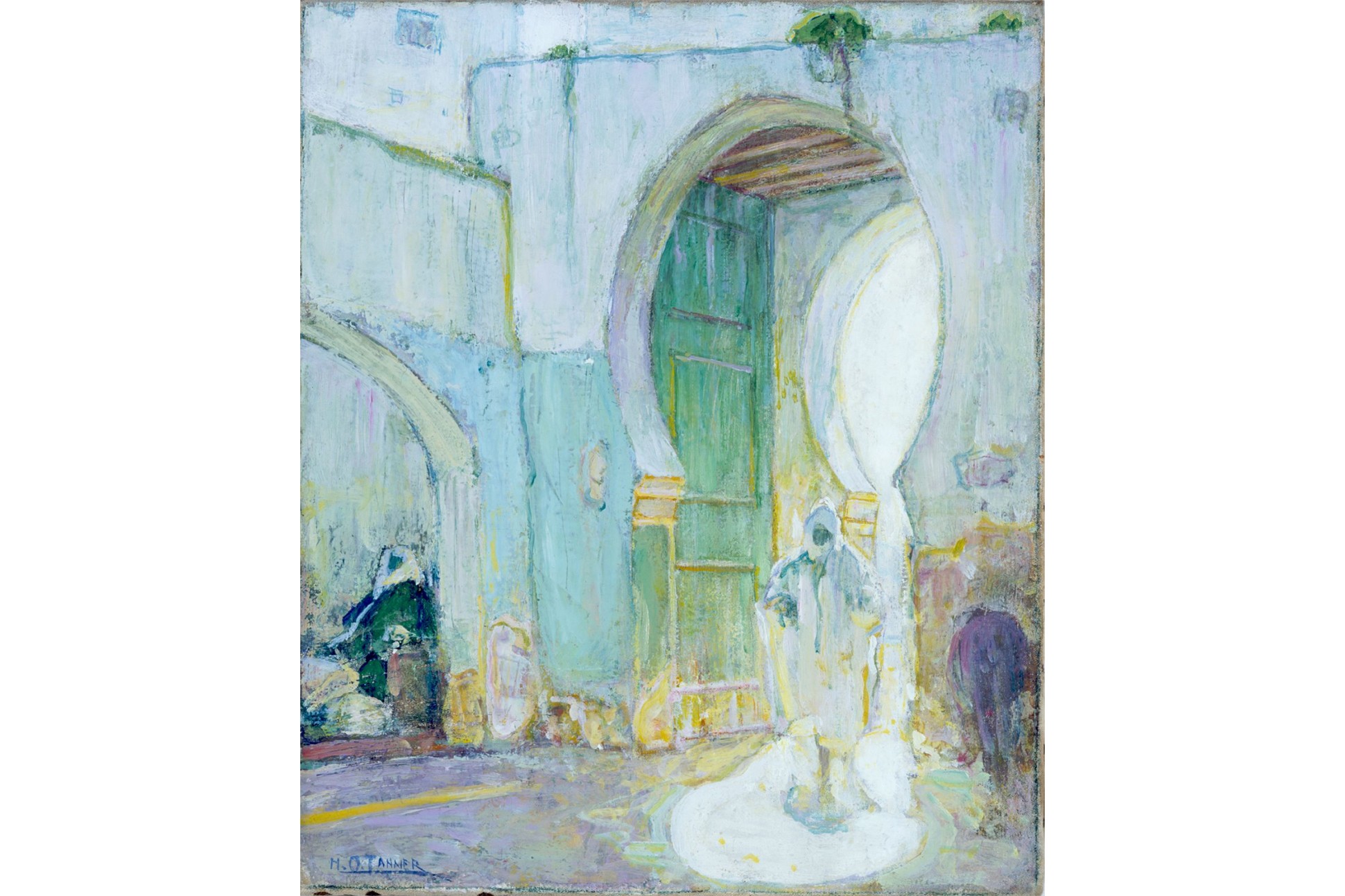

The sense of poetry in an artist’s work transcended the subject itself, even if it were sacred. Speaking of the works of the African American painter Henry Ossawa Tanner (1859–1937), Monroe observed how, If certain of [his] paintings are religious it is because they are infused with a quality of spiritual poetry and mystery, not because of the titles affixed to them. ... The special excellences which distinguish Mr. Tanner’s best work are its humane and poetic feeling.... About one of Tanner’s Moroccan cityscapes Monroe gushed, I would rather have it and would get more religious inspiration from it than from any [image of a] saint.

An even higher order of praise for Monroe was likening a painter to an author. Monroe once described the American artist Albert Pinkham Ryder (1847–1917), whom she knew personally, as a poet-painter. On the New York Ashcan School realist George Bellows (1882–1925), whose work was being shown in Chicago, she speculated, If he is a poet, his muse is epic rather than lyric, which she describes in terms of journalism: Of [his] city pictures “New York” tries to tell the whole story, and even though not quite free from reportorial slam-bang, it is a poetic telling of it, something beyond mere illustration to speak for us to a quieter age.

For Monroe, some artists, like the French realist-impressionist Jean-François Raffaëlli (1850–1924), surpassed even poets in the lyrical beauty of their locale-specific imagery: No painter, no writer of prose or verse, ever felt more keenly the charm of Paris, she said, or ever gave in his art with such spirit and humor and sympathy the flavor and poetry of the place.

Monroe sometimes even compared painters to the most canonical authors. In a review from April 1910, she called the United States landscape painter, Chicagoan George Gardner Symons (1861–1930) a descriptive poet. He might be likened to Wordsworth because of his sense of nature’s sternness, of a certain heroic bigness and simplicity in [nature’s] movements.

About another artist, Monroe claimed that the former School of the Art Institute of Chicago student Lawrence Mazzanovich (ca. 1872–1959) was a lyric poet, a kinsman of Keats singing to the nightingale under the moon, or of Shelley running with the west wind over the hills, following with one of her poetry-inspired descriptions: His pictures are songs, expressions of lyric rapture; songs sometimes of pure joy, again of wistful tenderness, but always inspired by the haunting and elusive beauty of the world.

Monroe sometimes cited actual lines of verse to praise a painter. About the American Childe Hassam’s impressionist art at Chicago’s Thurber Gallery, for instance, she quoted evocatively from Shakespeare that his best art[could] carry us further than our hopes. Now he has mastered his style, made it as obedient as Ariel was to Prospero, as swift “To fly, to dive into the fire, to ride/On the curled clouds.” He has become a worker of miracles, and to be a worker of miracles is to be a great artist. For Monroe, Hassam’s was not just a magical success; it was a national achievement on the level of The Tempest. [T]hese pictures are so American; their beauty is ours, is expressive of our landscapes and cities, our feeling, our life.

“We Must Be Citizens of the World”

In many of Monroe’s art reviews, she pleaded with readers to appreciate the work of American artists. She was writing at a time when the nouveau-riche of the United States were conspicuously absorbing and displaying their appreciation for European culture at the expense of more proximate artists. Monroe insisted that United States patrons consider the work of their compatriots and challenged the notion that artists had to accrue European accolades to “prove” their worth.

Time was when public opinion in this country underestimated American artists who did their work at home, when it demanded foreign honors as a kind of diploma or certificate before being convinced that an artist had really grown up. For a decade or more after the Columbian exposition the superstition lingered that any American artist must show proofs why he should be permitted to stand on the same plane with a real Frenchman, German, Englishman, or other scion of more favored races; nothing but foreign medals and other honors would convince his fellow countrymen of his success.

But neither did she discount those United States artists working abroad, for to do so would be equally unjust.

Now there is some danger of the pendulum swinging too far in the other direction, Monroe warned, of our being unjust to those American artists who live abroad. ... Such an attitude is as provincial as the other, and quite unworthy of American artists, critics, commissioners, art juries, hanging committees and exhibition officers.

Perhaps reflecting her own avid travels, Monroe felt that art and inspiration inherently involved and required worldliness. Art is a wanderer, she stated, a cosmopolite. She has work for her favored sons to do here and there and everywhere, and it is no sin for them to live and labor wherever they feel the highest inspiration. Not doing so would show up in their art, she said. If all of our artists who have remained past the student period in Paris should suddenly pack up and come home ... American art in general would lose ... that intelligent and wholehearted cosmopolitanism which modern art, like modern politics, must feel and express.

In this review, Monroe’s plea switches to an internationalist perspective, where creative achievements will be judged by future generations.

We must be citizens of the world. None of us can shut himself up at home and pretend that his village or town or nation is all. What will come out of it in art or literature no one can tell until the twenty-third or the twenty-fifth century rounds up its predecessors. But it may be a bigger art and a bigger literature than our long subdivided and distracted world has ever known before.

This worldly consciousness and the importance of art’s responsiveness to more than the local was compounded by Monroe’s belief in the transformative expressiveness of art.

Monroe’s appreciation for more socially conscious works indicates a more engaged worldview. For instance, she deeply admired the worker sculptures by the Belgian realist Constantin Meunier (1831–1905), which were shown in 1914 at the Art Institute of Chicago. They depicted, she said, the modern democratic message of human brotherhood and the dignity of labor. Artistic subjects such as these were favored in the Progressive Era for their sympathy with the common man. In one review, Monroe quoted two contemporary poets––Meunier’s countrymen Maurice Maeterlinck and Émile Verhaeren—who also enthusiastically commended Meunier’s art.

In a review the following week, Monroe again expressed her appreciation for Meunier, this time quoting William Butler Yeats. The Meunier exhibition [at the Art Institute] reminds me of the advice given to poets by William Butler Yeats during his recent visit to Chicago, she mused, referring to a Cliff Dwellers banquet sponsored by Monroe and Poetry magazine. Monroe dramatically changed Yeats’s words to address visual artists:

If we may substitute the word “artist” for “poet,” [Yeats] said: “Real enjoyment of a beautiful thing is not achieved when an artist tries to teach. It is not the business of an artist to instruct his age. ... His business is merely to express himself, whatever that self may be. The artist must put the fervor of his life into his work, giving you his emotions before the world.”

Clearly, for Monroe, expression, emotions, and the depiction of a passionately lived and politically aware existence were the aims of both visual artists and poets. However, expressing her own appreciation and practices of art was not her goal; she hoped to spark her readers’ interest in the creative products of their fellow citizens.

“No Poet Can Sing On and On If No One Listens”

An early review from December 1909 represents Monroe’s most intense cri de coeur for an appreciation of American creativity. In what the headline described as a “sermon,” she chided American (and specifically Chicagoan) audiences who preferred the art and poetry produced in foreign centers. Gone was her patience with audiences who looked abroad for a cheap, cosmopolitan, or borrowed status. She called her readers to action:

It is time to protest against all this, to cry aloud, to shout a warning, to ring the bells of clamor in every steeple. Because this colonialism of taste is not only stupid, it is disastrous. It condemns our poets to silence—since no poet can sing on and on if no one listens; our painters to starvation or to compromise with commercialism, or else to foreign residence so that they can win reputation at home by securing honors abroad.

In this period, Monroe was also thinking about the plight of unsupported poets and was scandalized by those conditions that would lead her to found Poetry three short years later. Once she did, she was then faced with deciding to publish American, European, and/or expatriate poets and vowed to showcase and pay those poets for their labor and cultural contributions.

After she became the founder-editor of Poetry in 1912, Monroe’s art reviews show an increasing sensitivity to the politics of recognition for all artists. In several, she discusses juries, the process by which artworks were selected for exhibition. Art societies, academies, juries, officials, tend, as everybody knows, to harden and fossilize. Men in control like to keep control, and naturally prefer to honor those in sympathy with their views. Moreover, Monroe observed, the entire process was tainted. It is an open secret, confirmed by details in the talk of the studios, that art politics, rather than merit, has governed most of the highest awards in our various cities during the last few years.

Juries were not only self-serving, Monroe believed them often wrong in their choices altogether. She reviewed an exhibition in France and lamented,

In sifting out the good, one is filled with pitying wonder for the bad. Where did all these banal pictures and statues come from, and where will they go to? What hours of enthusiasm, what months and years of ingenious labor have been wasted in achieving them, what disappointment and despair will follow them into oblivion! And by what perversity of indulgence could any jury have admitted to this annual gathering place of the world’s art so many works of misdirected effort which neither Pittsburg, New York, nor Chicago would give space to?

Monroe questioned the institutional authority of juries altogether. She recounted a conversation with the Spanish painter Joaquín Sorolla, saying, But why have juries? Instead, Let everything in, everything; otherwise, you may miss the best of all. This sentiment looks forward to her famous “open door” policy for submissions to Poetry.

Despite this barbed (and, I feel, deadly accurate) criticism of juries, jurists were also “editors” of a sort who chose which pieces to show. Painters who serve upon juries do so at a considerable cost to themselves, she reflected, for the benefit of institutions or societies holding exhibitions, and, indirectly, for the benefit of the public. Her criticism of juries notwithstanding, Monroe urged patience when judging artworks and poems. She mistrusted the first impression and the impulsive choice. It is a pity that prizes cannot be given at the end of an exhibition instead of the beginning, she imagined. This sentiment rhymes with some of her editorial decisions, including poems like “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,” which she and her team might have rejected after the first reading.

After publishing several issues of Poetry, Monroe had learned the difficulties of editing and curation, which humbled her and made her sympathetic to institutional gatekeepers including critics. She realized that the mere printing of one’s opinion increases its carrying power but never its value. The writer of criticisms, the professional opinionater, may always be wrong. Still, she never lost sight of the critic’s attempted impartiality and claimed that a critic’s business is with the artist’s ideas, not with his own. Whether she fully succeeded or not, Monroe applied this ethos to her stewardship of authors’ verse in Poetry, where she had to make difficult, even canon-shaping decisions.

“Freer and Vaster Dreams”

As early as 1909, Monroe was consolidating her convictions about the intensely reciprocal relationship between audience and the artist.

The beautiful expression of our own life, our own thought, feeling, imagining, aspiration—that is the art which belongs to us, which should appeal most strongly to us. And it is only by responding enthusiastically to this appeal that any people can get the best of which its artists are capable. In art, science, invention, philosophy, the great epochs come when a strong creative impulse meets an equally strong impulse of sympathy.

We might read in this an early version of Poetry’s motto, borrowed from Walt Whitman: “To have great poets, there must be great audiences too.”

Monroe, who wrote in the age of Thomas Edison when new technologies were changing everything and quickly, bravely foresaw how artists and poets might be relevant heroes if they were responsive and better appreciated:

Today in America the Inventor is thus stimulated by universal appreciation, and what miracles we get from him—turbine power plants, wireless telephones, aeroplanes! Tomorrow we may be as potently interested in art, even in poetry, which is now the poor neglected Cinderella of the arts. And then also we may be granted miracles!

Like her hero in architecture, Daniel Burnham, Monroe imagined for American artists and their audiences a bold, inspired future:

[Society is] entering perhaps upon a new period of thought, a kind of mysticism founded upon larger knowledge and deeper science. Who can tell whether this new period of closer human fellowship, of freer and vaster dreams, will not prove the inspiration of a greater, more universal art?

To realize it, however, required avid cooperation between artist and audience. By praising the achievements of Americans, including women artists and artists of color, in her reviews and in the pages of Poetry, Monroe skewered prevailing biases in taste along with its controlling patriarchy. Altogether, her achievement in the Tribune reviews and in Poetry helped define the culture of Progressive Era Chicago and the broader literary and artistic world. Monroe’s vision of creativity—both its production and its reception––is as relevant to our own historical moment as it was at the turn of the 20th century.

Mark B. Pohlad (he/him) is an associate professor in the History of Art and Architecture department at DePaul University. He earned his PhD from the University of Delaware and teaches courses on modern and American art and on Chicago topics. In 2017, Pohlad facilitate the discussion of Harriet Monroe’s art...

-

Related Collections

-

Related Authors

- See All Related Content