Eleven Legends

The following essays are excerpted from the April 2023 issue of Poetry magazine.

A poet’s work—whether in celebration or resistance—does not happen in the ether. Like all other arts, poetry relies on reinvention and reimagination as much as it does reaction to the unique pressures, crises, and historical mores that mark the moments of our lives we manage to remember. Poetry is built on pieces of the interior even as it is rendered for the public. It’s deeply communal even as it serves as a single trumpet amid the bandstand. The art of poetry is, at its heart, about elevating—language, sound, heroes, and myths—and the issue you are holding celebrates the 2022 Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize recipients’ many different legacies of convening and uplift. In previous years, one poet was awarded this prize in recognition of a lifetime of resplendent and unparalleled poetics. This year, in honor of the 110th anniversary of Poetry, eleven poets were selected as a nod to the eleven decades of the magazine’s existence, and their work here is briefly introduced by friends and literary compatriots.

The living legends in these pages— CAConrad, Sandra Cisneros, Rita Dove, Nikki Giovanni, Juan Felipe Herrera, Angela Jackson, Haki R. Madhubuti, Sharon Olds, Sonia Sanchez, Patti Smith, and Arthur Sze—have been celebrating, protesting, emboldening, untangling, re-remembering, mythologizing, and stirring shit up their entire careers. They’ve been working for us and for our art symbiotically through a myriad of cultures and topographies. The word symbiosis comes from a Greek word that means “living together”—not living off one another, or next to one another, but in concert. So it’s not just the poets being honored in this issue; it’s the readers and all of us poets who have been transformed by their idiosyncratic wonders on and off the page.

Since my first issue as editor of Poetry, it’s not hyperbolic to say that every US poet we’ve published is somehow connected creatively to the eleven award recipients. This collection of poets has made it possible for the writers we’ve convened in the magazine to be brash, to be defiant in their lines, and to be loud in their vowels and consonants. To imagine or reimagine form and shape poetically. To demand acknowledgment of the culture and community fearlessly. The generosity of these Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize recipients over their writing careers (some of which span more than fifty years) has been its own kind of musicality, a new form of revelation, and the unexpected engine for contemporary poetics. Lucille Clifton once said, “Poetry is a matter of life, not just a matter of language,” and these eleven poets are manifestations of that ethos. They are the keepers and tellers. Their lives are lived poetry. — Adrian Matejka, editor of Poetry

CAConrad

[CAConrad: Selections]

CAConrad’s poetics is a form of presencing that insists on multiple ways to inhabit experience. A queer activist, a diviner, and a visionary from beyond the veil, Conrad brings shape to the whispers of the cosmos. Influenced by writers such as Emily Dickinson, Audre Lorde, and Eileen Myles, their thinking, teaching, and art-making participate in the search for hidden yet meaningful relationships between the world at large and the world of spirit.

Transformation is at the core of Conrad’s practice. As a generous and beloved teacher, their (Soma)tic Poetry Rituals are legendary, as is their love of crystals, which they often form into a crystal power grid in their pursuit of transformation. They assemble sites of the possible and create “laboratories of the future of wild unleashing,” to quote “Chocolate Crack on a Stick,” their ecstatic essay on liberation, love, and the imagination.

I think of CAConrad’s art and ways of being as interventions, creative acts that aim to restore conditions for regaining presence. You could say that CAConrad’s practice is a form of magical studies, a practice in dialogue with the ineffable. As a poet, they enact the role of the Magician and High Priestess at once. As Damian Rogers writes of these cards: Magician, a “pan-dimensional change agent,” and High Priestess, a “vibratory communion.” These were the representational figures Conrad drew in a tarot reading I gave them as they embarked on writing While Standing in Line for Death (2017), a book they wrote when they turned to writing and ritual to cure their depression after the murder of their boyfriend Earth.

CAConrad composes symbolic and mental landscapes that offer us a glimpse of what exceeds the reach of language. Their art is that of ritualized structures that make meaning out of rage and hopelessness; it shapes and transforms emptiness into meaningful correspondence. “Mine is a poetics of uncooperation for all the brutal strategies built to sustain capital gain,” Conrad once said. Against the dehumanizing conditions of the factory in all its forms, CAConrad invents ritual concerning places and creatures, politics and events, the dead here too, rallying cries. What I love most is that CAConrad makes possible a vision of the cosmos, in acts of transcreation, where words, sounds, and images might acquire the ability to remain open to action and insight, to shape new realities. — Hoa Nguyen

Sandra Cisneros

To understand Sandra Cisneros’s poetry, it is important to know that she grew up the only daughter among the seven children of a Mexican father and Mexican American mother. At that time, in the fifties and sixties, cultural prescriptions dictated she remain in the household until she became a wife and mother. She became neither. Instead, she left to study poetry at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, and in her twenties, thanks to arts grants, sojourned in Europe. Cisneros’s travels show up in her first full-length collection, 1987’s My Wicked, Wicked Ways: “Women fled./ Tired of the myth/they had to live.” These lines resonate with what she later called an “escape route” from patriarchy and the cultural legacy of her gender.

In 1980, Mango Publications issued Cisneros’s chapbook Bad Boys, a slim poetry volume that examines the lives inside a Chicago working-class neighborhood—a precursor to her classic novel The House on Mango Street (1984). That same year, Cisneros met Norma Alarcón, a PhD student, at the Midwest Latina Writers’ Workshop. Alarcón would become the founder of Third Woman Press, which championed Cisneros’s early work in its journal and published the first edition of My Wicked, Wicked Ways. The Workshop strived to write “outside cultural nationalist narrative” by decentralizing Aztlán, the mythical Chicano homeland. Cisneros would later write that she “was bullied by hard-core Chicano activists who thought my writing was not Chicano enough,” despite her references to pre-Columbian gods and use of Spanish colloquialisms. “I am evil. I am the filth goddess Tlazoltéotl./I am the swallower of sins./The lust goddess without guilt” are lines in her second full-length collection, Loose Woman (1994), that exemplify the mezcla of sexual agency and cultural heritage typical of her poems. Although published by a New York publisher, Loose Woman became the apotheosis of what Third Woman Press had sought to create: “a space for Latina self-invention, self-definition, and self-representation.”

A new collection, Woman Without Shame (2022), is Sandra Cisneros’s return to poetry. At sixty-eight, the poet writes about the admiration of the aging body as “a life lived,” the dalliances of her younger self, and her resettling as a successful artist in the Mexico of her “abuelos/Who couldn’t read.” The voice is assured, defiant, optimistic. In 2015, Cisneros spoke to the long gap between collections: “Poems were to be written as if they could not be published in my lifetime. They come from such a personal place. It was the only way I could free myself to write/think with absolute freedom, without censorship.” Liberated from expectations, Sandra Cisneros’s third poetry collection is just that: recalcitrant, vulnerable, guiltless. — John Olivares Espinoza

Rita Dove

[Rita Dove: Selections]

Rita Dove won the Pulitzer Prize when I was in elementary school, and she was the US poet laureate by the time I was in high school. From the first time a teacher told me Dove’s name, I have made it my duty to be a student of her work. I have learned that she uses the oddest pieces of the world and makes of them the stuff of lyric poetry. She comes to this through particular and peculiar language that does the work of observation and examination. In a Rita Dove poem every image is pinprick small, making for a stinging papercut that leads us to revelations as seductive as they are harrowing:

O why

did you pick that idiot flower?

Because it was the last one

and you knew

it was going to die.

—From “Heroes”

By 2004, in a prestigious PhD program for poetry, I was living that story so old to us now that we sometimes think of it as a cliché: the Black one, or one of the only Black ones, who is almost always offended. Students and teachers needed to touch my hair and to ask me to lead class when they bothered to put as broad a subject as “Black poetry” on a day of the syllabus.

Somewhere in all of this, Rita Dove appeared yet again to save my life, to remind me of possibility. As if her poems had not done enough work, she wrote a letter to Poetry magazine’s editor, published in the June–July 2004 issue. I had no idea that I needed someone to fight for me, that I needed to be reminded of my ancestry, that women like Rita Dove had always been writing with someone like me in mind. This letter did three things for me:

- It let me know that some of my feelings of invisibility had a lot to do with who I thought needed to be looking at me.

- It gave me a framework for what my life would become, not just as a poet, but as a kind of literary activist who understands that our beloved community of writers is yet a microcosm of a larger society. I would always have to be vigilant, prepared to say it when I saw us falling short, not just in our art but in our treatment and consideration of one another. And,

- It let me know that it was okay for me to expect everyone to prepare for and know the tradition from which I was born, as I have prepared for and know the tradition of John Ashbery and Robert Hass and Charles Wright.

The person, the poems, the genius. Poetry is ever indebted to Rita Dove. — Jericho Brown

Nikki Giovanni

[Nikki Giovanni: Selections]

Throughout her poetry, and in her poems here, Nikki Giovanni has metaphorically used cooking and food to explore human relationships. “Bay Leaves” describes the different experiences with food the poet has with her mother, her grandmother, and herself. As many other poems Giovanni has written affirm, her grandmother offered an important, significant counterpoint to her nuclear family. The most striking difference is how the speaker shifts from observer to participant; the poet is often an observer—of her mother and of her parents’ marriage. The third stanza describes the ingredients her mother uses to make greens and seems to refer to more than those ingredients in its closing lines: “Not everything together/All the time but all the time/Keeping everything.”

“Her Dreams” uses music, another recurring theme in Giovanni’s oeuvre, both to describe her mother’s dream of being a success through singing with her two daughters, and the poet’s own separation from her mother and sister, which is emphasized in the last two stanzas but also suggested earlier by the poet’s inability to harmonize with them.

“Her Dream #2 (Runner-Up)” explores the impact of segregation on the mother’s dreams of being a tennis star. The trophy she won for making it to the finals of “The Colored Tournament” was prized by the poet; even though the trophy was for being “Runner-Up,” her mother lost in the finals not to just anyone, but to Althea Gibson. Like so many other things valued by the poet, the “Runner-Up” trophy was broken by her father out of jealousy that he did not have such a prize. Despite her father’s destruction of the trophy, her mother remains a winner in her daughter’s eyes.

If the first three poems here all present the poet’s effort to understand her mother and her mother’s continued marriage to the poet’s father, the final poem asserts the truth of the children’s book her mother taught, The Longest Way ’Round (Is the Shortest Way Home). The poet finally recognizes that her parents’ marriage “Is none of your business” and that “Your parents don’t owe you anything.” In the end, what she actually wants is the memory of three things: “this Blue Book/With a wonderful title,” “My Mother West Wind Stories,” and her mother “singing/‘Time After Time.’”

Together, these poems describe a childhood that was lonely because the poet was outside the relationship her mother and sister shared; a childhood in which the poet was forced to be an observer—either by her family or as a self-employed survival mechanism; a childhood in which her father’s destructive behavior taught the poet that material objects do not matter. Yet, as the fourth poem’s final stanza asserts, her own values—developed, perhaps, in reaction to those of her parents—have resulted in happiness. — Virginia C. Fowler

Juan Felipe Herrera

[Juan Felipe Herrera: Selections]

The former US Poet Laureate Juan Felipe Herrera is an artist whose life and work have always been defined by motion. Born in Fowler, California, to a migrant worker couple, Herrera spent his early childhood moving from place to place in the San Joaquin Valley.

The Herreras finally settled in San Diego, California, when Juan Felipe was eight years old, and suddenly he became a “downtown boy.” After graduating from San Diego High School in 1967, he earned his BA from UCLA, and then was admitted into the graduate program in social anthropology at Stanford University. After securing his MA, Herrera was somewhat disenchanted with academia. He abandoned the doctoral program at Stanford and later joined the renowned Iowa Writers’ Workshop, where he obtained his MFA in 1990.

Herrera is an extremely prolific author. Beginning with Rebozos of Love (Tolteca Press, 1974), his first and extremely experimental chapbook, the body of work he has amassed now counts thirty-five books and spans all genres: poetry, novel in verse, young adult fiction, and children’s books.

As one of the pioneer artists of the Chicano Movement, Herrera’s early writings were inscribed within the cultural revival of pre-Columbian themes and motifs that defined that epoch, and then moved quickly into a broad exploration of contemporary urban life and social problems. The result has been a unique form of postmodern expressionism that incorporates elements from oral and written traditions, drama, music, and the visual arts. A free spirit committed to human rights and social justice, he has always resisted being labeled as a particular type of poet or constraining his works within any neatly defined genre. Indeed, his compositions defy traditional modes of analysis, and at times even strict classification as poems.

I once asserted that Herrera’s continuous process of maturation and the coherence of his overall poetic project assured him a prominent place in the history of Chicano poetry, and that “a correct appraisal of his contributions is long delayed.” But my early protestations, perhaps premature, have been amply answered over the years. The accolades Herrera has received to date are too many to list here. For me, the climactic moment came in 2015 when Herrera, after having served as poet laureate of California from 2012 to 2015, was appointed as US poet laureate from 2015 to 2017—the first Chicano and the first Latino to occupy these posts. One of his poems, “Sunriders,” which I was honored to translate, was included in the capsule of Lucy, the interplanetary spacecraft launched by NASA in October of 2021. A gentle, humble, and generous soul, Juan Felipe Herrera has always been in the vanguard of contemporary US poetry. — Lauro Flores

Angela Jackson

[Angela Jackson: Selections]

Angela Jackson’s imaginative writing elaborates on Chicago’s powerful mix of aspiration and desperation, especially on the part of Black Americans—those who made their way to the city during the Great Migration and those living in the legacy of that journey. Jackson, born July 25, 1951, in Greenville, Mississippi, is a true daughter of the Great Migration, and she expresses the lived and mythic experiences of that legacy in her seven poetry collections (full-length books and chapbooks), her many plays, and her novel, Where I Must Go (2009). Since 1971, she has built an extraordinary and necessary oeuvre from an education mixing the Organization of Black American Culture (OBAC) with her MA from University of Chicago and an MFA from Bennington College. At OBAC, Jackson found mentors such as Carolyn M. Rodgers, Jeff Donaldson, and Hoyt W. Fuller, who became lifelong advocates for her work.

Jackson’s poetry has received great recognition, starting with the Conrad Kent Rivers Memorial Award in 1973 to the Shelley Memorial Award from the Poetry Society of America in 2002. Dark Legs and Silk Kisses: The Beatitudes of the Spinners (1993) received the Carl Sandburg Award and It Seems Like a Mighty Long Time (2015) was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize. Her beloved and bedeviled Chicago remains her greatest muse and it is fitting that she was named Illinois poet laureate in 2021, a post that was once held by Gwendolyn Brooks, whom she chronicled in A Surprised Queenhood in the New Black Sun (2017), an important literary biography. The importance of African diasporic sensibilities comes through in Jackson’s innovative use of myth, particularly in the “Wishbone Wish” section of her 2022 collection, More Than Meat and Raiment. Receiving the Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize, one of America’s most prestigious literary awards, is a fitting honor for a poet who in an elegy says:

I am a memory borrower, brothers and sisters.

I will keep you safe and sacred. I am a keeper.

I can take up where you left off.

—From “The Memory Borrower”

— Patricia Spears Jones

Haki R. Madhubuti

[Haki R. Madhubuti: Selections]

In 1969, Gwendolyn Brooks remarked that Haki R. Madhubuti, then known as Don L. Lee, sat “at the hub of the new wordway.” He was mingling with the likes of Amiri Baraka, Lucille Clifton, Jayne Cortez, Larry Neal, Kalamu ya Salaam, and Sonia Sanchez to define the poetic substance and energy of the Black Arts generation. Influenced largely by Detroit doo-wop and jazz, and continually considering the relationship between poetry and music, he published the iconic volumes Think Black (1967), Black Pride (1968), Don’t Cry, Scream (1969), and We Walk the Way of the New World (1970), all from Broadside Press. These works display the rhythm, humor, social insight, and vernacular sensibility that made him one of the nation’s most-read poets and led to his inclusion in over one hundred anthologies. They also portray his commitment to reworking, as he put it, “old stereotypes and themes and images to bring us more understanding of ourselves as individuals and as a group of fragmented, oppressed people.”

It is hard to miss the influence of Langston Hughes on the young Madhubuti. It’s especially evident in the relationship between Hughes’s “I, Too,” and Madhubuti’s “They Are Not Ready,” the earlier poet’s general determination giving way to specific revolutionary expressions by the latter. Indeed, while still a teenager, Madhubuti purchased and studied a secondhand copy of The Poetry of the Negro, the landmark collection edited by Hughes and Arna Bontemps in which Hughes is featured.

Madhubuti’s latest work, Taught by Women: Poems as Resistance Language (Third World Press, 2020), is a love letter, a Black valentine to women of all stripes who have contributed positively to the person he is. No introduction to Madhubuti should fail to mention his decades-long friendship with Brooks, about whom he writes:

with the wind in your hand,

as in trumpeter blowing,

as in poet singing,

as in sister of the people, of the language,

smile at your work.

—From “Poet: Gwendolyn Brooks at 70”

We can wish the same for Haki R. Madhubuti. — Keith Gilyard

Sharon Olds

[Sharon Olds: Selections]

To read a Sharon Olds poem is to peer into some first instance of creation: to see that spark that must have been both the inevitable beginning and ending of all life. A few elements come together—crash together, really—forming one thing that is the root of all things. Call it love. Call it our humanity. Call it grace or light or clarity. Birth. Death. Desire. From her first book (Satan Says, 1980) through her recent fifteenth (Balladz, 2022), Olds writes poems that seem to conjure and reconstitute the sparks that animate our lives.

One remarkable feature of her poems is the way she manages to look incredibly closely at an object or emotion and then casts the scope of her attention so broadly as to sweep the whole world into her lines:

Dear dirt, I am sorry I slighted you,

I thought that you were only the background

for the leading characters—the plants

and animals and human animals.

It’s as if I had loved only the stars

and not the sky which gave them space

in which to shine. Subtle, various,

sensitive, you are the skin of our terrain,

you’re our democracy...

—From “Ode to Dirt”

In another poem, a cedar box becomes a gateway to radical honesty about the nature of rage and grief and love. In another, tiny strips of cardboard offer a path toward self-love and forgiveness. A spoon becomes a conduit for intersectional awareness in yet another poem. And elsewhere, the tampon, “unhonored one,” helps Olds rewrite rules regarding what and who we honor. The poet Hafiz once wrote, “Good poetry makes the universe admit a secret.” Over and over, this is what poetry by Sharon Olds does.

Olds frequently takes as her subject the daily, often banal aspects of life, and from these quotidian details she reimagines what splendor can look like and mean. A diaphragm. A penis that reminds her of a slug. Childbirth. A son’s seizures. The tools we use to punish and prod: “In my mother’s house, it was a whiskered hairbrush,/its tortoise stripes beautiful as a honeybee’s fur,” Olds writes in a poem from Arias (2019) called “Sprung Trap.” And the tools we employ for praise. In one poem from Balladz, she writes of choosing not to kill a spider: “With a juice glass/and a large postcard,/I trapped the glorious dancer.” Sweat and desire. Graying hair and hangovers. The inglorious aspects of our lives and our deaths are made, by her graceful, careful lines, worthy, wonder-full, and new. — Camille T. Dungy

Sonia Sanchez

[Sonia Sanchez: Selections]

When the sun yawned and stretched this morning, Sonia Sanchez was eight decades deep into imagining a world where there is justice, peace, and beauty. Born in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1934, nine years later she was in the flow of the Great Migration. She arrived in New York, and discovered a library in Harlem where there was food for the brain, the soul, the imagination. Sustenance that helped her grow into a giant.

Sonia Sanchez is a unique yet familial voice on the page, in the classroom, and on stage. The distinct voice of her work is flavored with the literature and music of her people and the world. Reading her work makes you want to experience her performance. Her performance leads you back to the page to contemplate the meaning and the magic of her words. She is a revered poet in so many communities, especially Black communities where her poems are heard in churches and schools, women’s clubs and HBCUs. She gets hailed in the store, restaurants, and on the street, celebrated especially by young women. Her life and poems are a song of what is possible.

An activist, artist, and intellectual, she chose to stand against the poison of racism, sexism, and militarism. She often paid for it with joblessness and financial precarity for her family. She never wavered, always determined to use her great gifts in service of the ideas she committed to. Mentored by women who came before her, Gwendolyn Brooks and Margaret Walker and others looked after her as creative spiritual mothers. Her poems flowed unabated in the Black Arts Movement and beyond. The explosion of Black artistic expression in the movement carried her into a multidisciplinary and multicultural family of artists. Poets and dramatists, dancers and painters, photographers and filmmakers, teachers and laborers, musicians, scholars, and students all continue to expand the incredibly large extended family of Sonia Sanchez. Although she retired from the classroom years ago, she continues to teach. She is a mentor to new generations of poets and artists who are creating, teaching, leading, and building the world she envisions. — Michael Simanaga

Patti Smith

[Patti Smith: Selections]

I’ve spent a good part of my life loading and unloading U-Hauls stuffed with band equipment around the United States and overseas. The forty-five minutes of performing music each night was the bonus in between. I caught the music bug early: The Doors, Sabbath, Hendrix, Zeppelin, etc. Eventually that led to The Stooges, Betty Davis, Bad Brains, Gun Club, Mudhoney, Suzi Quatro, and more obscure music for the heads.

But my first exposure to Patti Smith wasn’t her music; it was her poetry. When I discovered she was co-lyricist for Blue Öyster Cult’s (all hail the umlaut!) “Career of Evil,” and was personally and artistically involved with Fred “Sonic” Smith of the MC5/Sonic’s Rendezvous Band, I became curious. Then I discovered she was a poet. This being pre-Internet times, I sprung into action, except, and importantly, instead of record bins, I went straight for the bookstore shelves.

I was as into poetry as I was into music, but I didn’t know where to go beyond my English textbooks. When I devoured Smith’s words, high school me experienced the same thrill as reading William Blake, Sylvia Plath, and John Keats. But there was something more. Smith’s poems name-checked Jim Morrison, Brian Jones, and Judy Garland, alongside Rimbaud and Voltaire. This was poetry I understood. And she could be so direct, owning her space and power like in these lines from her poem “jeanne d’arc,” “I want my cherry/squashed man/hammer amour,” or from “k.o.d.a.k,” “pleased to leave my monogram. close up shot/of my steady fist. I’m cool as menthol.” Smith was my gateway to contemporary poetry. She changed my life with her unabashed and lyrical honesty.

Smith has done it all—music, poetry, prose, visual art, black-leather lifestyle—on her terms. With every literary or rock and roll breakthrough she’s made, she’s won something for us. She brought us along with her. Her poem “A Pythagorean Traveler” from Auguries of Innocence: Poems (2005) holds the secret of the universe: “Beauty alone is not immortal/It is the response, a language of cyphers.”

This past fall, she read in my hometown. A friend attended with her mother. My friend told me—more like testified to me—how Smith had been a lifelong gateway between herself and her mother. How Smith’s words were part of them, and that they felt they were a part of her words. Her words had given their relationship shape and strength, and, as individuals, sanctuary and confidence against the world. Thank you, Patti Smith, for giving us so much beauty, and most of all, for giving us the cipher for all the things we have a hard time sharing with each other. — Chet Weise

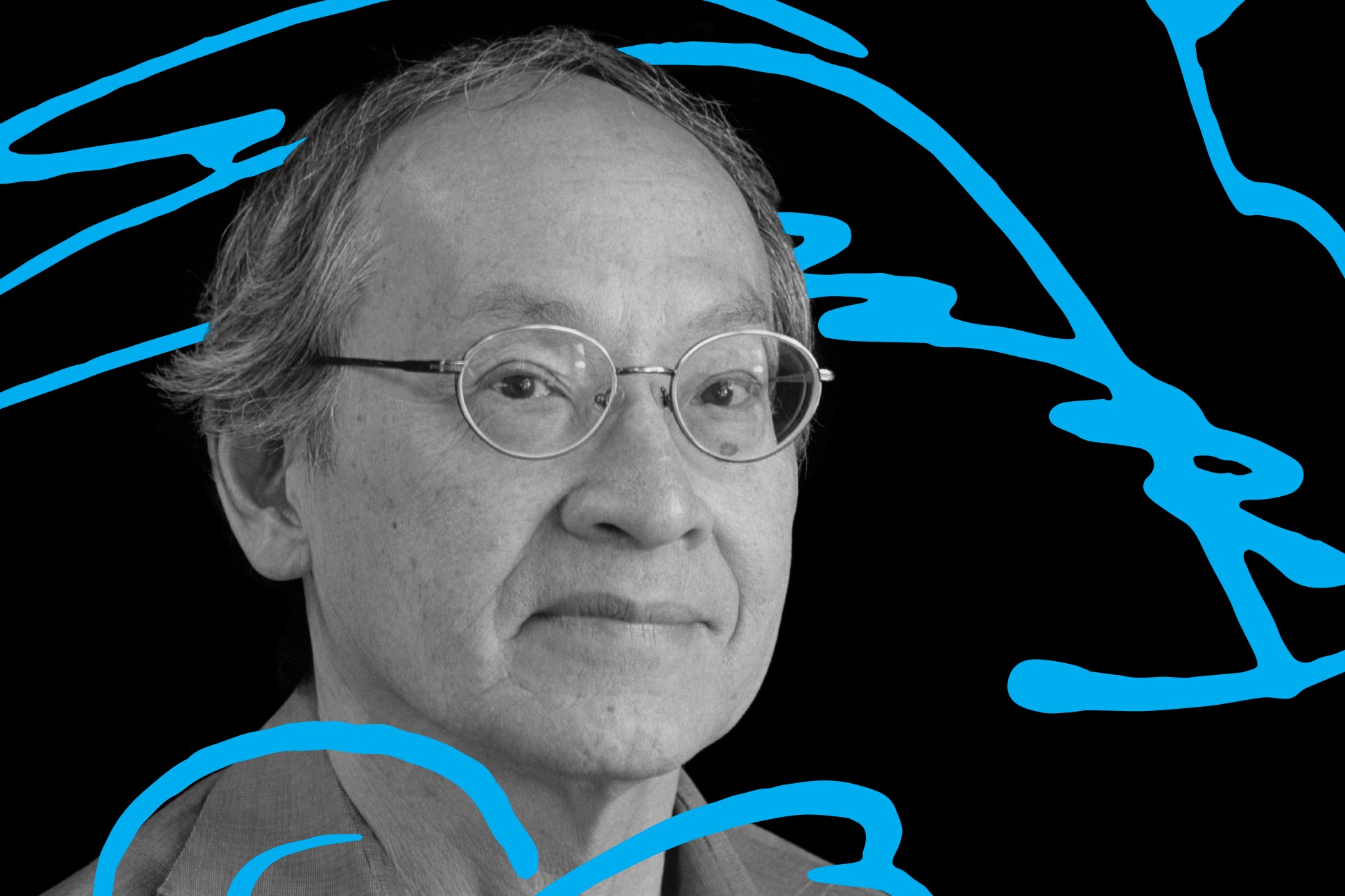

Arthur Sze

[Arthur Sze: Selections]

To Arthur Sze, dear friend, Keeper of the Acequia, now I remember discovering your poems in 1985 in Tyuonyi, that small literary magazine published by the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA). The magazine’s name, the Keresan word for meeting place, was an apt venue for your work, which, already in the early eighties, derived its energy from the meeting of unlikely assemblages of natural description, conceptual statements, scientific observation, questions, and exclamations. I tracked down your first two books, Two Ravens and the revised edition of The Willow Wind, both from Tooth of Time. Your poems and translations made reference to reservations, desert, aspen, New Mexican Native tribes, but also to Mexican history, intimate relationships, and classical Chinese poets. To wit, your roots may have been local, but your cultural perspectives were, from the start, international.

The poet CD Wright, my wife and coeditor, and I were both so keen for your work that we wrote you in 1985 to solicit the manuscript of River River, which Lost Roads Publishers brought out in 1987. That collection includes your first long serial poem, boding the modality that would define your later work. The title for the book was a reduplicative, a signal feature of many Asian languages. We agreed to your striking choice for a calligraphic cover, and we sold out three editions.

And so, dear Arthur, began a friendship that has lasted for forty years, during which time we’ve hiked through Anasazi ruins in Chaco Canyon, picked blackberries in the hills of Petaluma, gone quiet together at the feet of a giant wooden Buddha, taught side-by-side, eaten meals, yammered about poetry, and met with wildfire scientists. I can’t forget the image I have of finding you asleep one early morning in our guest bed—lying on your back with your hands folded over your stomach in transcendent peace like a trim, reclining bodhisattva. You have a characteristic equanimity that has always grounded me and served as a kind of model for my own aspirations as man and artist.

The influence your work has had on contemporary poetry is vast, not only through your support of writers at IAIA and your signal translations of Chinese poets, but also in how your body of work has helped foster what is now called ecopoetry and, in philosophy, object-oriented ontology. Philosophically and sensorially alive, your poems have been for me and for so many readers a codex of thought and imagination for our time. A cornucopia of rendezvous. Seductive, endearing, alienating, vibrating structures, your poems have come to be models for processing—as feeling, as sensorial, intellectual, and linguistic experience—our brief, shimmering encounter with others and the inscrutability and legibility of what we call the world. — Forrest Gander

The editorial staff of the Poetry Foundation. See the Poetry Foundation staff list and editorial team masthead.

-

Related Authors

-

Related Collections

- See All Related Content