An Interview with William J. Harris

Howard Rambsy II: How would you describe your poetry?

William J. Harris: My poems are as straightforward as I can make them. I come from William Carlos Williams and Langston Hughes. I want my poems to make the reader feel, understand, and laugh—it is nice when a poem does all three. My poems are often political in their indirect way. I am old-fashioned in that I want to create beauty in my poems. There is so much beauty in Baraka’s poems, especially the late ones, for example “Ballad Air & Fire” for his wife Amina. Now, I am trying to understand why artists like Picasso, who can paint beautifully, painted so many ugly figures. Would he have been a lesser artist if he continued to just make beautiful paintings? I often find it better to look at paintings instead of poems when I have general questions about art.

HR: You’ve been actively writing poetry for over five decades now. What’s really different about sitting down to write a poem in 1968 as opposed to, say, now in 2022?

WJH: In 1968, I thought of myself as a full-time poet who wrote criticism sometimes. Over the years, I wrote fewer and fewer poems and more and more critical prose—people were asking me for prose, not poetry. And something else was going on: I wasn’t taking my poetry seriously. I didn’t write big dramatic poetry like Ginsberg’s or Baraka’s. I wrote short poems which were often comic, serious but in a different way from most of my fellow poets. I was trying to tell the truth but in my own way. Recently, I have gone back to poetry and started thinking of myself as a poet again. If you don’t worry about what people think, it’s fun to make a poem. I remember very clearly, years ago, when I finished writing “Modern Romance”—after rereading it, I laughed out loud. That was a great pleasure. And in the last couple weeks, after finishing a poem about Alice Neel, I felt great all day. From now on I am going to write poems and criticism and this time neither is going to smother the other.

HR: Speaking of your poem “Modern Romance,” which focuses on the idea of robots and artificial intelligence, I’m curious about how technology has affected your approach to poetry composition over the decades.

WJH: Technology has had a great impact on my writing and thinking. I still start new prose and poetry on a legal pad, preferably yellow, with my favorite pen of the moment. For quite a while I have been revising on my iPad and I love it. It is so easy to write and rewrite there. (And spell-check is my friend.) I am very happy on the iPad, and I think it has made me a better writer because it is so easy to revise.

I know there are many bad things about Facebook but it has been great for me. It lets me talk to my friends about poetry and ideas and introduces me to new things I wouldn’t have otherwise encountered. I am a big believer in randomness and learning—randomness lets you get out of your narrow world. I have learned a great deal about painting from looking at all of these images that appear on Facebook. It really adds to my museum viewing experience. And friends keep posting all these great articles. It is a place I can share my ideas about the arts and particular artists and thinkers.

HR: I want to ask about your involvement with Robert O’Meally’s Jazz Study Group at Columbia, from its founding in 1995 to the development of Columbia’s Center for Jazz Studies. I know you became involved with the Jazz Study Group because of your long friendship with O’Meally. But it seems that your identity and reputation as a scholar, more so than who you were as a poet, shaped your contributions to those critical conversations and projects on jazz.

WJH: Yes, you are absolutely right. It was a scholarly undertaking; it had nothing to do with my poetry or being a poet. Yet it was a great experience, a wonderful opportunity, where I learned so much about music. There were great people at those meetings, such as John Szwed, Mark Tucker, Herman Beavers, Margo Jefferson, Ann Douglas, Farah Griffin, John Gennari, Brent Edwards, and Fred Moten. I met Fred there, and I was blown away by his brilliance and sweetness. It continued my jazz education, which started at Stanford with conversations with fellow graduate student Nate Mackey, undergraduate Bob O’Meally, and Jones Lecturer Al Young.

The Jazz Study Group was essential in laying the foundations for the field of present-day jazz studies—much of the most important writing on jazz today is being done by members from that group. To me, all the arts are related and learning about another helps you understand your own art better. So, in a way, the Jazz Study Group has made me a better poet.

HR: Throughout much of your career, you’ve gotten a chance to reside in dual spaces as a scholar-poet, teaching African American literature courses on the one hand, but also teaching creative writing courses. Why do you think it was important to do both?

WJH: I have been very lucky because I get great pleasure from teaching both literature and creative writing. I really enjoy the conversations in lit classes where students exchange ideas. Teaching lit courses lets you think seriously about great literature and the society that it comes from—Black lit is a wonderful literature to study in context. And reading books over and over makes you a better reader. It is like how I look at paintings repeatedly, to truly see them. It is serious business. Wonderful questions come up and haunt us all. Once, in my contemporary poetry lit class, I taught Robert Creeley’s Pieces (1969), and we couldn’t figure out how the pieces—the poetry fragments—fit together. During the summer, one student from the class wrote to me and said that he had figured it out. I was delighted that he had taken the question so seriously and was haunted by it.

What is great about teaching creative writing is you can help young poets find out what they can and want to do. It was a mixed blessing to teach both, though, since I had a PhD as well as an MA in creative writing. The faculty members in the English department wanted a critical book, not a small book of poems—they did not care much about poetry. I am so glad I taught both Black and white lit—it was such a rich experience. And it is such a joy to watch talented poets grow and have careers.

HR: You’ve attended quite a few art exhibits over the last decade or so in New York City, and you’ve been incorporating what you’ve seen into the poetry you’re writing. Can you speak a little on the process of writing and publishing poems about the art you’re viewing in New York?

WJH: First of all, there are lots of great museums in New York. If you don’t go on Saturday or Sunday (when the museums are overcrowded) they are marvelous places to explore—there are unbelievable treasures, nothing else like it, and it is untimed. And God, the artists are magnificent and you can look at them as long as you want, and if you don’t get enough, you can come back the next day.

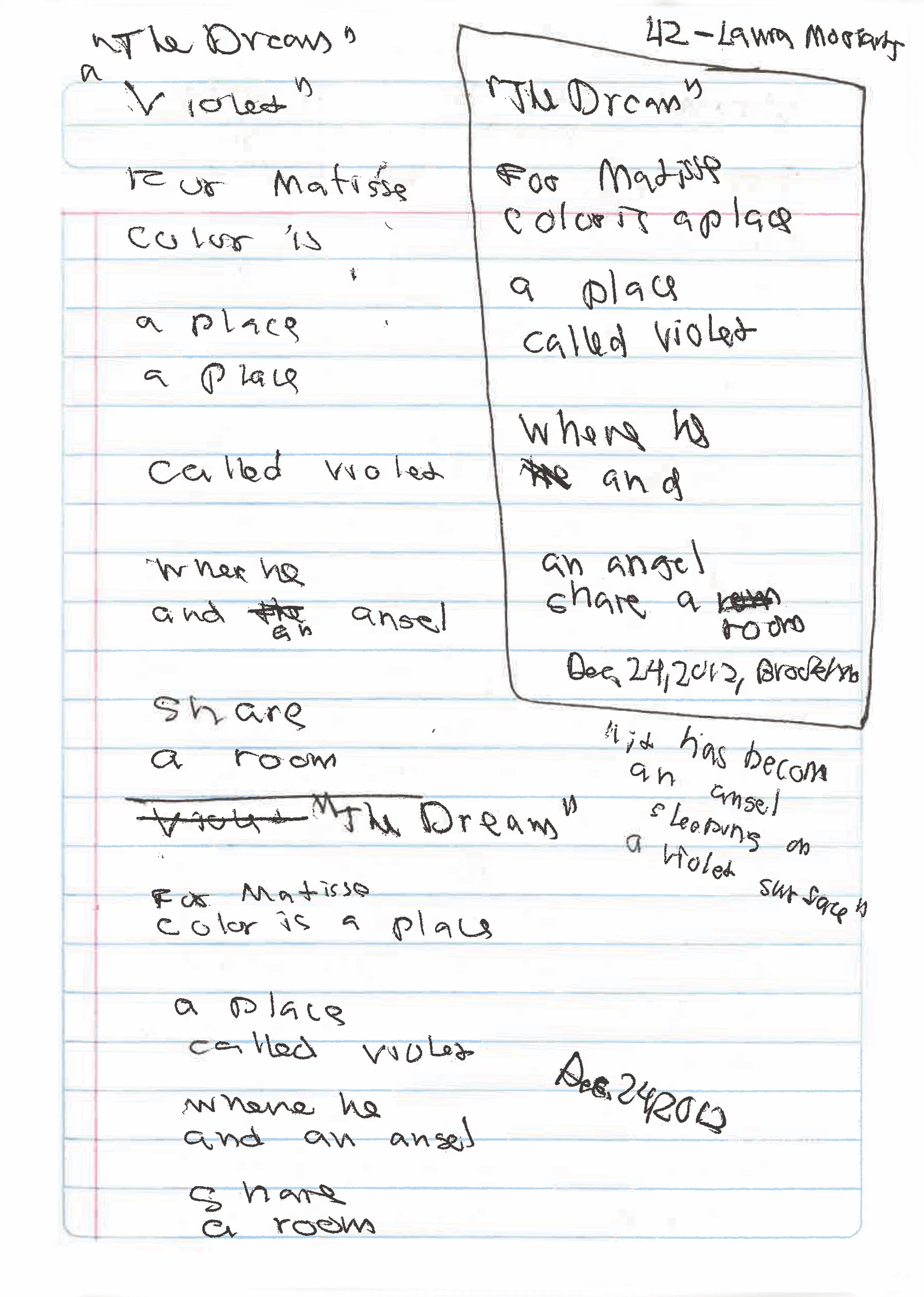

You can develop a real relationship with the art. It is interesting to see what artists working in a different medium from yours do in their work. In many ways visual artists are not that different from poets; they are also commenting on the world through their art. I am blown away by their visual creation of beauty. And, of course, artists help you see. This process of viewing art is so profound I end up recording it—first in my portable journals and later in poems. I guess this is my way to pay homage to the form.

HR: You have these drawings or sketches from exhibits in your notebooks, alongside the words you’ve jotted down. When did this habit of drawing and writing emerge? And how does it fit within your processes as a poet?

WJH: As with all my museum work, it was a natural process—it just grew out of the situation. I was thinking about the paintings, observing the paintings, and I wanted a record of them. So I started drawing in my notebook, which I always carry with me. Before I started drawing, I tried to record my interactions and observations with the paintings in words. I also did the drawings to keep the paintings straight, which is which.

In the early sixties I discovered the great poet Kenneth Patchen, who was a poet of word and image—he was a modern Blake. His early word-image poems were crude, but he got better, in fact, more than better over time. I loved the humor and whimsy that his drawings contained. For a while I got talked out of his greatness. At Stanford, I wrote two word-image poems: “My Blue Period” and “My Friend, Wendell Berry.” Wendell was my poetry teacher at Stanford and is a wonderful and kind human being. I submitted the poem to workshop. Looking back, that seems like a funny thing to do. What is interesting about these poems is their playfulness—their creation of a multifaceted comic and fantasy world. They are different from my word-only poems; well, perhaps the science fiction poem “Modern Romance” is a kin.

I started drawing in journals in 2017. I think I would have started earlier if I hadn’t wanted to express everything in words. I always wanted to draw and felt I wasn’t good enough. There is always that question: what is good—what constitutes good art? Part of being an artist is finding your own sense of what is good. This is a very difficult thing to do.

My copying of the paintings let me into the creative process and added a dimension to my enterprise. It was like how writing poems helps you teach poems better—you have this sense of how to make a poem, a process which involves both making sense and making form. Making a poem is both an intellectual process and a formal one. You may be a very different poet from the one you are teaching but in a general way your sense of how to make a poem helps you and the students understand the poem under study. It is like how you visit a fellow carpenter and observe his/her/their work. Even if the carpenter is very different from you, you still have a sense of how the house goes together. Or you say, I have no idea how it fits together—let us start there.

William J. Harris is an emeritus professor of American literature, African American literature, creative writing, and jazz studies. He taught at the University of Kansas, Pennsylvania State University, and Cornell University, among other universities. He lives in Brooklyn, New York.

Howard Rambsy II, a distinguished research professor of literature, teaches classes on African American literature and comic books at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville.

-

Related Collections

- See All Related Content